The prospects and perils of participating in China’s New Silk Road

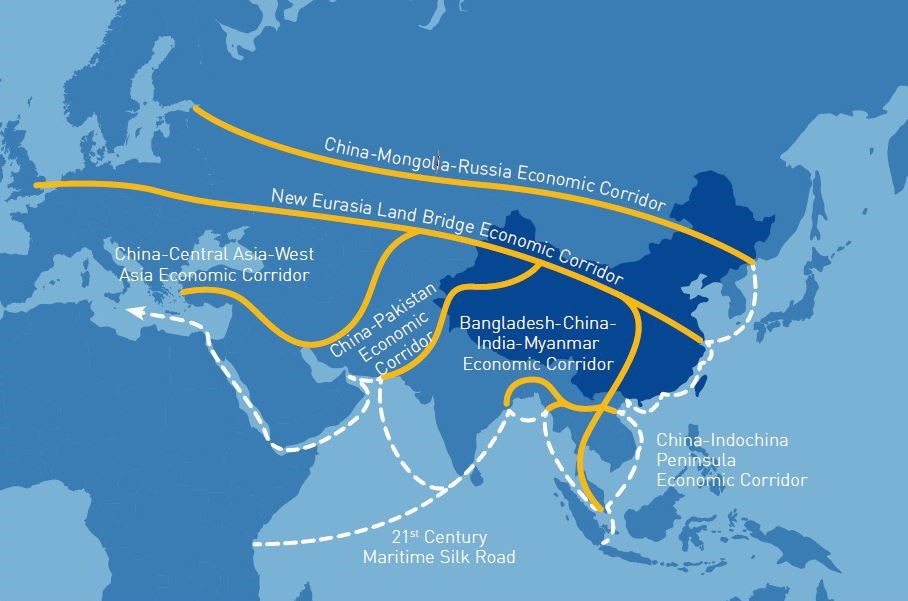

Initially announced in October of 2013 in Kazakhstan and Indonesia by Xi Jinping, China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), also known as One Belt One Road (OBOR), is a combination of two initiatives: a 21st Century Maritime Silk Road and a Silk Road Economic Belt both depicted in the map below. The BRI has now become the crown jewel of Xi Jinping’s foreign policy such that it has been enshrined as the cornerstone of China’s 13th Five Year Plan (March 2016), and is now included in both the Constitution of the Communist Party of China and the National Constitution of China (October 2017).

The maritime “Road” is presented by Beijing as a major opportunity for consumer and industrial firms. Excluding China, it accounts for 63% of the global population and 44% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The landlocked “Belt” connects two of the world’s largest economies: China and Europe. The route is predicted to emerge as a major logistics corridor while also claiming to offer significant energy and mining opportunities.

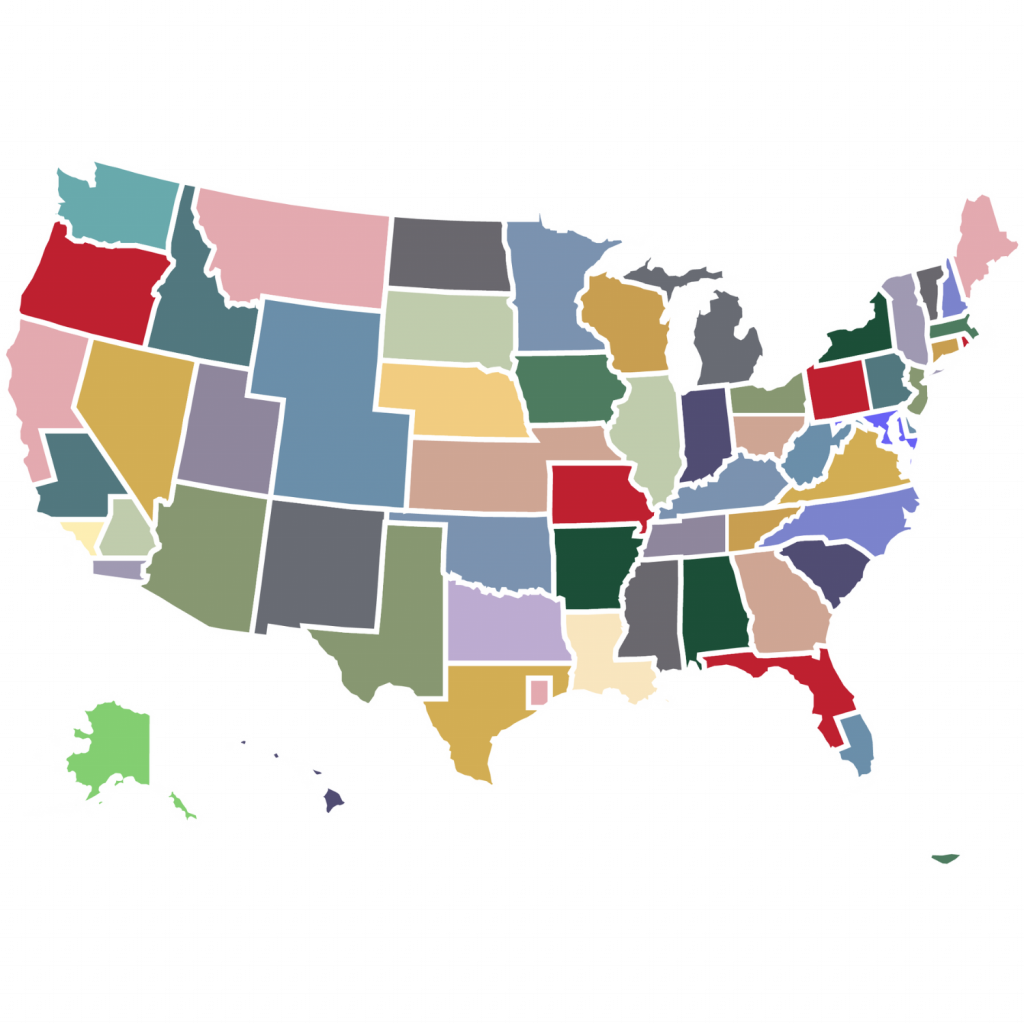

The BRI is a global development strategy adopted by China involving infrastructure development and investments in some 152 countries. This includes international organizations throughout Asia, Europe, Africa, the Middle East, the island countries of the Pacific, and the Americas (Central and South). This infrastructure development includes physical entities such as railways, bridges, roads, etc., as well as digital. The Digital Silk Road (DSR), is a subset of the Belt and Road initiative. The DSR consists of financing for purchases of Chinese telecommunication equipment, fiber-optic cables, and surveillance systems. These items are purchased by governments and the private sector around the globe. In many countries, such purchases prompt understandable fears about importing the intrusive characteristics of the Chinese political system and the risk of Chinese espionage.

The map depicted above is simply a start and does not lay out the full scope of the BRI as it is currently conceived in Beijing.

Finally, there is an Arctic “leg” of the BRI that has yet to be announced.

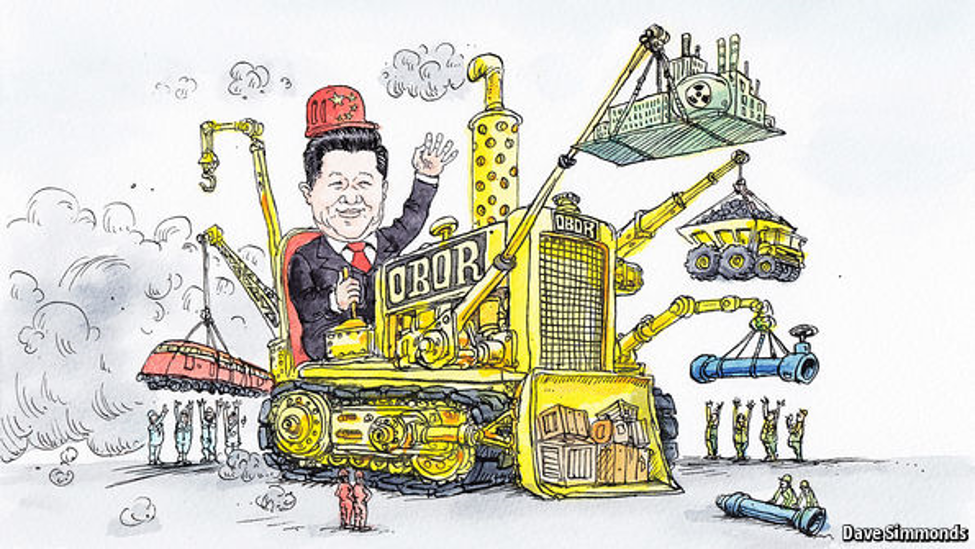

There is a geopolitical side to the ambitious economic expansion of China’s “reach” as it seeks to build out its own supply chains and economically dependent countries in what Beijing perceives as a post-American world. The Belt and Road Initiative seeks to foster investment connections and an infrastructure architecture, both physical and digital, that would tie a number of countries to Beijing both economically and politically. One example of the political muscle China has generated with the BRI is that United Nations has so far been unable to pass any negative resolutions against China relating to the Uyghur camps in China’s resource-rich Xinjiang province.

Although the BRI initiative provides funding for investment that is often only of marginal economic value, it is perceived by some to be filling a void left in many areas of the world by Western powers. It is also contributing to a path of dependency for poorer economies that may not be able to extricate themselves from Chinese influence in the future (“debt trap” diplomacy). Sometimes the dependency is real where the debt burdens newly incurred by relatively poor countries within the program are alleviated by the Chinese regime in exchange for further contracts or political concessions.

Opportunities

- As exporter and suppliers. Companies can supply advanced construction equipment, machinery, tech equipment and solutions along with other cutting-edge solutions for infrastructure projects. There has already been much collaboration between Chinese companies and foreign multinationals. In addition to suppliers of construction materials, those specializing in providing equipment (both in the tech sector and non-tech as well) can expect to be involved.

- As investors. Companies can invest in bankable infrastructure projects, either by co-investing with Chinese companies or by investing in a partnership with existing Chinese entities, such as the Silk Road Fund. Commercial banks have been invited to participate. The right terms for both multilaterally funded and privately financed projects will need to be carefully negotiated.

- As experts in international project management. A company can share its expertise, especially in working with complex, large-scale BRI projects in remote locations, which requires managing multiple stakeholders. Chinese State Owned Entities (SOEs) in particular will need advice and guidance on how best to navigate local laws, regulations, and business environments, as well as how to work with local players and workforces. There may be more in-depth partnership opportunities for companies that specialize in professional services and project and commercial management.

- As partners in engineering, procurement and construction (EPC). If a company has recognized international experience in large-scale infrastructure projects, or in dealing with local EPC companies of the BRI countries, it could partner with firms from China by sharing their experiences in designing and developing infrastructure in less developed countries. Partnerships such as these can enable a company to gain access to new markets along the Belt and Road routes.

- As operators of management resources. A company can bring its operational experience in managing effectively, profitably, and sustainably to new settings. Beyond technology, Chinese company leaders are interested in management experience, especially within emerging economies.

- Asset allocation. Companies and individuals can divest assets to enterprises operating along the Belt and Road routes. Chinese or local companies that are seeking to enhance their existing capabilities.

Important Tips

- Emerging Markets Risks. Companies will face challenges and potential risks with the BRI, any of which could lead a company to make major investments without sufficient payoffs. Operational issues associated with any emerging economy, and the risks that come from poor execution.

- Special risks on the digital or tech side of the BRI. The “Digital Silk Road” aspect of the BRI seeks to embed Chinese 5G networks that will only support Chinese 5G compatible solutions, applications, operating systems, e-commerce platforms, e-government platforms, Internet of Things (IoT), as well as the national defense systems of the host country. Firms that are or wish to become involved in this aspect of the BRI need to be especially wary of hacking into their own systems along with the potential for intrusions, interceptions, planting and housing Chinese doomsday malware across a spectrum of digital devices operated by both your firm and those of the host country. The embedding of Chinese tech equipment along the digital Silk Road also means that the lucrative Chinese export of the “soft side” of the related services that necessarily accompany such equipment sales. The export of U.S. services along the Digital Silk Road is going to be largely, if not completely, foreclosed. There is also the potential for reputational and relationship damage to your company from its participation in the potential compromise of the host country’s economic, business, and defense sectors to consider.

- Understand that the BRI is a top down policy of the Chinese Communist Party. This means top-down policies and priorities can shift.

- Some projects may simply lack commercial viability.

- Political and Geopolitical challenges. Projects often extend through several countries, BRI projects have the potential to caught up in territorial disputes or regional power plays. Partnerships with state-owned enterprises may reduce the control that companies would otherwise have. Proposed projects may stall or be canceled for political reasons.

- Long periods for capital investment projects. Projects are vulnerable to geopolitical developments including changes in government, policy shifts, and feelings of enmity toward China. An example, in Sri Lanka a change in the presidency in 2015 caused a yearlong delay in the development of a port facility in the capital city Colombo.

- High Level of Trust and Commitment needed for cross-border projects. Trust at this level can be challenging and time-consuming to establish. If approached correctly, these investments could encourage local reforms that would attract much-needed foreign investment and participation.

- Investment Exposure. The BRI is a debt-financed, development initiative. The ability of a host country to repay its loans should always be questioned, especially by private investors. Investment exposure will also be affected by China’s efforts to build trust with other countries, particularly those whose skepticism is based on previous interactions.

- Lack of transparency. Many BRI projects feature opaque biddingprocesses for contracts and financial terms that are not subject to public scrutiny.

- Potential environmental risks. BRI projects lack, in certain instances, lack adequate environmental assessment which have caused severe environmental damage.

- Significant potential for corruption. In countries that already have a high level of corruption, BRI projects have involved payoffs to local officials. Companies should continue to follow the United States’ Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. Professional advice here is critical.

- Importance of negotiating adequate dispute resolution process. The default BRI provisions that call for dispute resolution to be handled within China should be avoided.

- Consideration for the potential public relations challenges. Attitudes towards China are shifting, both in the U.S. domestic as well as certain international markets. Consideration should be given as to the potential for PR challenges. Companies should be aware of possible negative reaction.

If your firm’s interest or inclination is to seek involvement in these types of international business opportunities, we would encourage you to give serious consideration to looking for opportunities within the competitive response to the BRI by the United States. As a consequence of the new Build Act passed by Congress in the Fall of 2019, the setup and funding of its new U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, along with the reconstituted and reauthorized U.S. Export-Import Bank (along with other funding sources for both U.S. and foreign borrowers), there is funding available to support well-planned and commercially viable U.S. private/public partnership infrastructure projects (both hard infrastructure as well as digital) in underserved/developing markets worldwide.

David F. Day, Co-Chairman, NADEC Policy Committee