By: Scott Lincicome, CATO Institute

Source: thefederalist.com/2015/06/09/top-nine-myths-about-trade-promotion-authority-and-the-trans-pacific-partnership/

The current debate over Trade Promotion Authority proves, once again, that the classic description of the anti-globalization movement—as “largely the well-intentioned but ill-informed being led around by the ill-intentioned and well informed”—still holds true. Despite the tireless efforts of trade policy experts to explain why TPA and the U.S. trade agreements it’s intended to facilitate are, while imperfect, not a secret corporatist plot to usurp the U.S. Constitution and install global government, myths and half-truths continue to infect traditional and social media outlets.

Because these myths—originating with the same old anti-trade bedfellows that have been with us for decades—have duped a lot of good folks who are otherwise predisposed to support liberty and free markets (including some(link is external) in Congress(link is external)), and because the House of Representatives is poised to vote on TPA in the coming days, here is one last debunking of the top nine myths about TPA, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), and U.S. free-trade agreements (FTAs) more broadly.

To save some time, you can skip to your favorite myth by clicking on the links below.

Myth 1: TPA and U.S. FTAs are unconstitutional and undemocratic!

Totally false. Cato’s Bill Watson and I explained(link is external) this at length in The Federalist last year, but here’s former Attorney General Ed Meese to reinforce(link is external) our conclusions:

Constitutional law professor John O. McGinnis also recently reviewed TPA(link is external) and concluded that TPA “simply permits Congress under its ordinary procedures to commit to a future majority vote of Congress to vote up or down on an agreement that the President has negotiated. Representative democracy is thus served by the later vote on an agreement whose text is known.” And then there’s the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1890 case of Field v. Clark(link is external) approving the constitutionality of an analogous law—the McKinley Tariff Act of 1890, which granted the president even more authority than TPA. It was no big deal.

Finally, it’s important to reiterate that, contrary to some claims, FTAs are not treaties(link is external) (which are typically “self-executing,” require two-thirds approval by the Senate, and have the force of law upon ratification). They are “congressional-executive agreements” that, even after being signed by the president, have absolutely no legal force until they are converted into implementing legislation (which would amend current law), passed by Congress, and signed into law by the president. Such agreements have for decades been used by the United States for many different issues, including trade liberalization, and U.S. courts have repeatedly rejected(link is external) constitutional challenges thereto. In short, a constitutional argument against TPA requires you to reject over a century of precedent, the repeated rulings of U.S. courts, and the opinions of even the strictest of constitutional scholars.

Myth 2: TPA grants the president new and unlimited powers!

Totally false. As already noted above (and reiterated here(link is external) by Cato’s Dan Ikenson andhere(link is external) by the Congressional Research Service), Congress under TPA retains total control over the international trade authority granted to it by Article I, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution. Any trade agreement negotiated by the president (which he has constitutional authority to do under Article II) still must be approved by Congress.

As noted(link is external) by the CRS, “TPA reflects decades of debate, cooperation, and compromise between Congress and the executive branch in finding a pragmatic accommodation to the exercise of each branch’s respective authorities over trade policy.” It represents a “gentleman’s agreement” between the legislative branch and the executive branch—with the former promising the latter “fast track” rules for the requisite congressional approval of an FTA, if, and only if, the latter (i) agrees to follow a detailed set of congressional “negotiating objectives” for the agreement’s content; and (ii) engages in a series of consultations with Congress on that content. As discussed more fully below, each branch of government retains its constitutional authority to abandon this gentleman’s agreement, but doing so will essentially kill any hope of signing and implementing new FTAs. So, with limited exceptions, Congress and the executive toe the line.

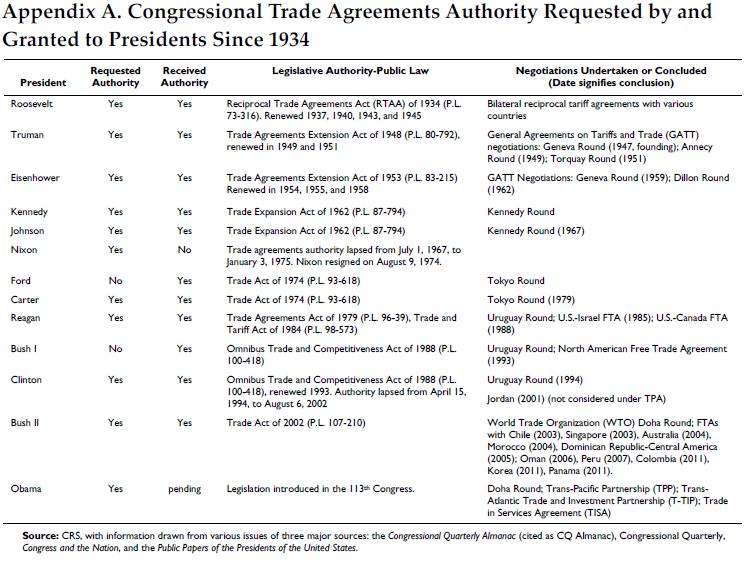

Because neither branch gets expansive new powers or short-changed, Congress has granted every U.S. president since FDR some form of trade negotiating authority (source(link is external)):

Pretty boring when you think about it, huh?

Myth 3: TPA sets legally binding congressional rules for USTR and U.S. trade negotiations!

Mostly false. As already noted, TPA sets congressional negotiating objectives on a range of issues (some more palatable than others), but, contrary to the statements of TPA antagonists and even some supporters, these objectives are not legally binding on the executive branch. Instead, the president retains his authority to negotiate with foreign governments, and, as Meese notes(link is external), that’s a good thing: “under well-established constitutional rulings, it would raise serious constitutional concerns for Congress to try to mandate the President’s negotiating positions.”

The president and his U.S. trade representative thus technically have discretion to ignore these objectives, but doing so would obviously jeopardize any final congressional vote. As the CRS explains(link is external):

To take the fullest advantage of these benefits, Congress, drawing on its constitutional authority and historical precedent, defined the objectives that the President is to pursue in trade negotiations. Although the executive branch has some discretion over implementing these goals, they are definitive statements of U.S. trade policy that the Administration is expected to honor, if it expects trade agreement implementing legislation to be considered under expedited rules [i.e., ‘fast track’].

The negotiating objectives constitute one part of the gentleman’s agreement between Congress and the president: “follow our wishes when you negotiate, and we’ll limit our meddling when a final deal is struck.” If the president doesn’t follow them, then the deal is off.

Which brings us to…

Myth 4: Once TPA is approved, Congress will be powerless to stop TPP or other FTAs!

Totally false. Not only does the latest version of TPA include new language expressly stating that the House or Senate can dismantle the “fast-track” rules(link is external) for various “disapproval” reasons, but—even more importantly—Congress has always retained this power because it has plenary authority over its rules of procedure, including “fast track.”

The new TPA, like previous versions before it, acknowledges this fact in Sec. 106(c)(link is external), which states that the fast-track rules are enacted as “as an exercise of the rulemaking power of the House of Representatives and the Senate,” but “with the full recognition of the constitutional right of either House to change the rules (so far as relating to the procedures of that House) at any time, in the same manner, and to the same extent as any other rule of that House.” The CRS summary(link is external) of TPA reiterates this fact: “Congress reserves its constitutional right to withdraw or override the expedited procedures for trade implementing bills, which can take effect with a vote by either House of Congress.”

Such power is not merely theoretical. It is precisely what then-Speaker Nancy Pelosi did(link is external) to the Colombia FTA in 2008 after President Bush submitted its implementing legislation. Her move effectively dismantled the “fast track” procedures and thus delayed congressional consideration of the agreement indefinitely.

In short, Congress retains total control over the FTA implementation process under TPA and can only be bound by the “fast track” rules if it wants to be bound.

Sensing a theme here yet?

Myth 5: TPP is being negotiated via a dangerous and unprecedented level of secrecy!

Totally false. Probably the most-repeated myth right now isn’t even related to TPA but instead to the TPP, which is still being negotiated. According to the anti-TPA script, the TPP is so secret that nobody knows what’s in it, and—much like Obamacare legislation—nobody, not even Congress, will know what’s in it until the agreement is passed into law. Once again, however, nothing could be further from the truth:

- First, Obama’s USTR and Congress have been consulting on the TPP since December 14, 2009, when then-USTR Kirk notified(link is external) Congress that President Obama intended to enter into TPP negotiations. USTR then held initial consultations with Congress in 2010(link is external) and, according to a January 2015 fact-sheet(link is external), has since held almost 1,700 congressional briefings on TPP alone. USTR also previewed various TPP proposals with key congressional committees before taking them to our trading partners. (Odd that the TPP talks have been going on for six years, but the vast majority of these “secrecy” complaints have only emerged in the last few months, huh?)

- Second, USTR has provided(link is external) “access to the full negotiating texts for any Member of Congress, including for Members to view at their convenience in the Capitol, accompanied by staff members with appropriate security clearance.” This access began in 2012, and several House members and senators—both supportive of TPA (like Mike Lee(link is external)) and opposed (like Sens. Jeff Sessions and Elizabeth Warren(link is external), as well as Rep. Rosa DeLauro)—have reviewed the draft negotiating texts. Moreover, the level of security surrounding these TPP texts isn’t part of some scary Obama administration plot; it’s set by Congress (which, as you’ll recall, is controlled by Republicans these days). A U.S. government official confirmed to me that “the Senate and House security offices determine the procedures for viewing classified material in the Capitol reading room where the TPP text is kept for Members—not the administration… some people claim that it’s more difficult to view military or intelligence information, but it’s all subject to the same rules that are set and enforced by Capitol security.”

- Third, USTR has engaged the public on the TPP via published reports and “stakeholder meetings(link is external)” with groups like labor unions, consumer groups, and, of course, corporations and trade associations. Some of these stakeholders have evenreviewed(link is external) the negotiating texts and US proposals. Admittedly, the official texts aren’t available to the general public, but this is common practice for all FTAs (as a quick Google search reveals(link is external)) and for good reason: just like other high-value negotiations among private parties or governments, revealing draft proposals before a deal is struck emboldens the opposition, undermines the parties’ negotiating positions, and exposes negotiators to public scrutiny over provisions that might not even be in a final deal. Publishing draft FTA texts would make completing a deal difficult, if not impossible, and it’s thus no coincidence the most vocal advocates for “full transparency” in free trade negotiations are actually those most opposed to free trade(link is external).It’s also important to understand just how unoriginal this “secrecy” canard is:

Yes, protectionists have been using the same “secrecy” lines for over 20 years. In fact, if you replaced “NAFTA” with “TPP” in those old Ross Perot commercials, they’d be almost indistinguishable from the ones on our TVs today.

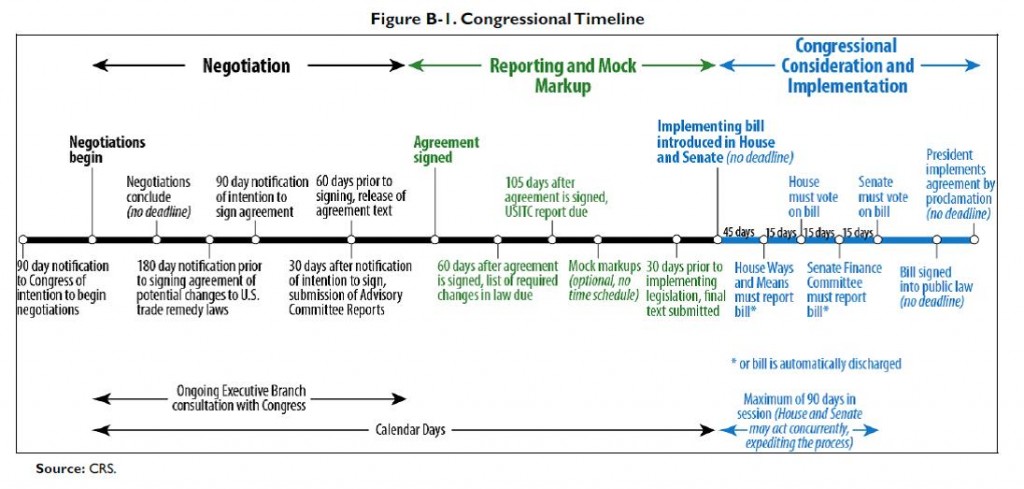

- Finally, unlike the oft-analogized Obamacare legislation, the actual text of any final TPP deal will be required by law to be publicly available (online) for months—yes, months—before Congress votes on it. As you can see from the table below (source(link is external)), under TPA the president must make the entire text of any trade agreement, including TPP, available to the public for 60 days before he can even sign it.Once it’s signed, Congress will have weeks, maybe months, to scour the deal, hold “mock markups” in various committees, and suggest changes to the agreement before the president sends Congress legislation implementing the FTA for a final vote. Also, within 105 days of the FTA’s signing, the U.S. International Trade Commission must issue a report on the deal’s economic impact—again prior those bills being submitted to Congress. And once the bills finally are submitted, Congress will then have up to 90 legislative days (which is like five months in normal human days) to review the bills and hold final votes.

Bottom line: when or if TPA is passed, the general public will have months—and if the presidential elections interfere, maybe years—to review the TPP before Congress acts on it. Think that’s crazy? Well, it’s precisely what happened to U.S. FTAs with Colombia, Panama and South Korea, which were signed by President Bush but sat around (online) for years(link is external) before they were submitted to, and passed by, Congress in 2011.

Myth 6: FTAs, completed via TPA, undermine U.S. sovereignty!

Totally false, as Watson and I explained(link is external) last year:

FTAs embody unenforceable promises governments make to each other. Domestic governments—here, Congress—retain the sole authority to ignore those promises and violate international commitments, and they (unfortunately) do so frequently(link is external). Foreign governments cannot force their trading partners to comply with the terms of an FTA—the only extra-national consequence of a violation is that other parties to the agreement may abrogate their commitments in a commensurate amount (e.g., by raising tariffs on imports from the United States from levels that were lowered in the FTA). Moreover, every U.S. trade agreement permits the parties to act outside the agreed disciplines in the name of, among other things, national security, public health and safety, or environmental protection. Thus, the idea that TPA and FTAs violate U.S. sovereignty or regulatory autonomy is patently false(link is external).

These principles hold true for the TPP, including its dispute settlement and controversial “investor-state” provisions. Despite what Warren (and some media outlets(link is external)) would like you to believe, there is nothing—absolutely nothing—that can force the United States to comply with an adverse dispute settlement ruling issued under the TPP or any other U.S. trade agreement. Period.

But, hey, if you don’t believe me, here’s Attorney General Meese again(link is external):

Future trade deals would not be unconstitutional, nor would they undermine U.S. sovereignty, if they contained an agreement to submit some disputes to an international tribunal for an initial determination. The United States will always have the ultimate say over what its domestic laws provide. No future agreement could grant an international organization the power to change U.S. laws.

A ruling by an international tribunal that calls a U.S. law into question would have no domestic effect unless Congress changes the law to comply with the ruling. If Congress rejects a ruling or fails to act, other countries might impose a trade sanction or tariff, but they are more likely to impose high tariffs now without any agreement. The fact remains that no international body or foreign government may change any American law. Moreover, Congress may override an entire agreement at any time by a simple statute. Nations also may withdraw from international agreements by executive action alone. That is one reason why such agreements do not interfere with the underlying sovereignty of each nation to chart its own course in the world. In short, the U.S. Constitution and any laws and treaties we enact in accordance thereto are the only supreme law of our land.

Myth 7: TPP is a secret backdoor for a parade of horribles (and TPA lets that happen)!

Totally false. Various politicians and pundits have sought to arouse suspicions by claiming, among other things, that TPA will permit President Obama to bypass Congress and use the TPP as a backdoor to, among other things, lawlessly expand immigration, curtail gun rights, or restrict Internet freedom. At this point, however, I hope you can see just how ridiculous these claims are. Regardless of the issue, the fact will always remain that nothing can be implemented via the TPP unless Congress agrees to implement it via a formal vote.

This would include things like new work visas (something that U.S. FTAs haven’t actually done for years now) or Internet regulations or gun rules or minimum wages or whatever: it all has to become law before it has any legal force, and the only people making law are Congress (and, again, according to their own procedural rules). So, if in the TPP the president committed the United States to toss every AR-15 into the Atlantic Ocean, those guns aren’t going anywhere unless Congress formally agrees, subject to all of the constitutional, procedural, and transparency rules already discussed.

And, really, do you think this Congress is going to do anything of the sort? Really? (For more specific debunking of these crazy ideas, go here(link is external), here(link is external), here(link is external) and here(link is external).)

We still don’t know precisely what’s in the TPP, and final judgment—by Congress and the public—should therefore be withheld until we do. But the idea that TPP, empowered by TPA, will grant President Obama any new legal authority to ignore or change U.S. immigration or gun or whatever laws without Congress is simply ludicrous.

Myth 8: FTAs (and free trade generally) benefit large corporations at the expense of working people!

Mostly false. There is little doubt that FTAs benefit some U.S. corporations and workers, while harming others—that’s kinda free-market competition’s thing.

In general, however, the corporate winners (who tend to be in growing, innovative industries) from U.S. FTAs outnumber the losers (who tend to be in archaic, uncompetitive ones). And every legitimate economic analysis of the TPP confirms(link is external) this general rule. FTAs also contain rules and exceptions for well-connected stakeholders. As I’ve repeatedly discussed, this is a big reason why FTAs are “third best” option(link is external) for U.S. trade policy.}

Nevertheless, there is also little doubt that (i) FTAs are pretty much the only trade liberalization game in town these days; (ii) while unpalatable, the cronyist exceptions in U.S. FTAs, are relatively minor compared to the overall liberalization; and (iii) the biggest winners from such liberalization aren’t corporations or the mega-rich, butconsumers, particularly poor ones.

(More here(link is external).) These gains wouldn’t be possible without FTAs (as much as we free traders wish they would be).

Thus, the idea that FTAs like the TPP, or any other reduction in global trade barriers, benefit the 1 percent at the expense of working class is just not true. Indeed, as we at the Cato Institute are constantly pointing out(link is external), the real cronyism in trade policy takes place on the anti-trade side of the ledger: corporations and unions lobbying government to shield them from free-market forces, always at consumers’ expense. It’s precisely for this reason that many of the U.S. lobbying dollars(link is external) spent on TPP aren’t from pro-export mercantilists (although there are plenty of those, too) but from those anti-competitive industries (autos, steel, textiles, sugar, etc.) and unions that are seeking to scuttle the deal or secure their own special exemptions.

Myth 9: TPA doesn’t matter!

Mostly false. Look, in an ideal world, all of these trade deals would be totally unnecessary: every government in the world would lower its trade barriers, kill its subsidies, and trade freely across borders, thereby enriching us all in the process. But that’s not our world. And even though some pro-TPA rhetoric is exaggerated, the legislation still has value for at least one big reason: U.S. trading partners take it seriously and won’t sign off on a final deal with the United States until TPA’s in place.

Indeed, over the last few months, officials from Japan(link is external), Canada(link is external), and Chile(link is external) (among others) have each made clear that their governments won’t finalize TPP until Congress passes TPA. And, again, it’s precisely for this reason that U.S. protectionists are spending major dollars to stop TPA: they don’t really think it’s going to destroy constitutional democracy and install a world government ruled by Emperor Obama; they just oppose free trade or the TPP. And they’re more than happy to prey on conservative insecurities to achieve their goal.

Since the 1940s, the United States, whether governed by Democrats or Republicans, has been the world’s leader on global trade policy. This leadership, due in part to President Obama’s mismanagement and disinterest, has waned in recent years. A defeat for TPA—and any resulting death of the TPP—would accelerate this decline.

There are legitimate (although not horrifying!) concerns about the contents of the final TPP deal, but it’s certainly not a harbinger of an economic or constitutional apocalypse. The American public should scrutinize the final agreement closely, but that won’t happen until TPA becomes law. For supporters of free markets, there’s no legitimate reason why it shouldn’t.

Scott Lincicome is an international trade attorney, adjunct scholar at the Cato Institute and Visiting Lecturer at Duke University. The views expressed herein are Scott Lincicome’s alone and do not necessarily represent the views of his employer.